In Ethiopia, Nigeria and Uganda, A Leadership Deficit Is On Full Display

By Faith Abiodun

Ethiopia is at war within its own borders, Uganda is experiencing its worst unrest in years, and Nigeria is implementing a dishonourable campaign of retaliation against innocent citizens who dared to speak up for the right to not be killed indiscriminately. Once again, a leadership deficit threatens to destabilize our fragile democracies as we attempt to reconcile the past with the future. Military dictatorships and autocracies were characteristic of an era long gone when the voices of citizens were subordinate to the wills of strongmen. And even if those years were uncomfortable, they were deemed perhaps necessary in order to birth a future devoid of needless bloodshed.

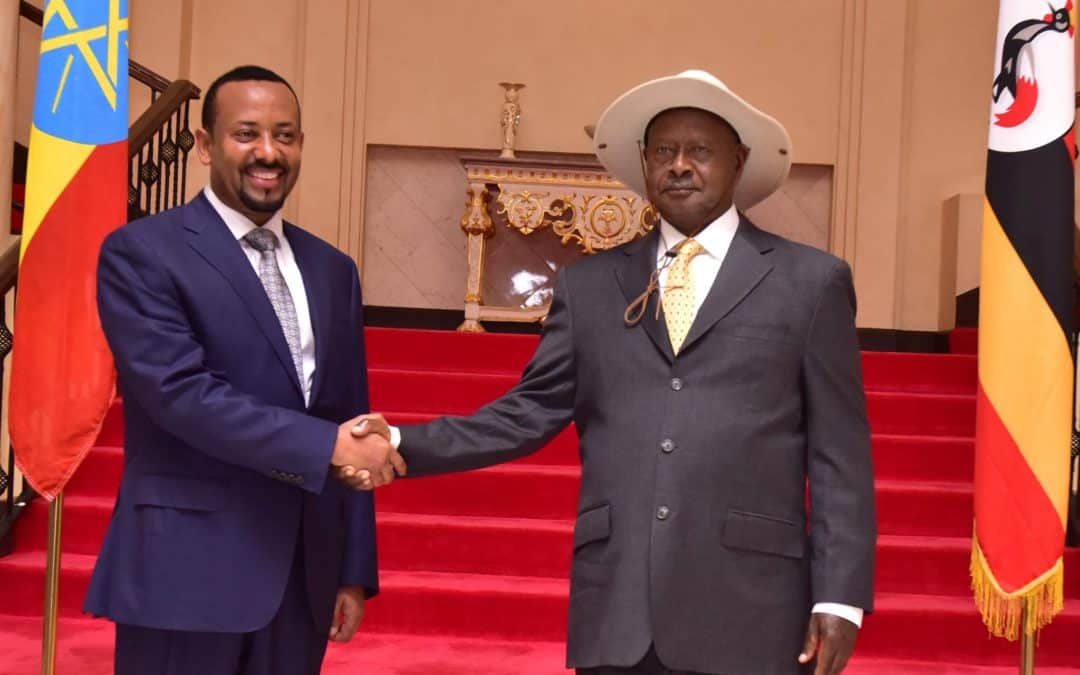

There was a promise of a better tomorrow, the dawn of which appeared to arrive in Ethiopia in 2018 when the fresh-faced Abiy Ahmed manoeuvred through the murky political waters of Ethiopia to emerge as Prime Minister. For 30 years, Ethiopia had maintained a tricky balance in its ethno-regional political dynamic that relegated smaller voices to the background and allowed an imbalanced coalition to thrive. Surely, it was only a matter of time before the militarily agile Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) took over again in some form, but Abiy Ahmed had an ace up his sleeve. In a seemingly coordinated move, he disbanded the very coalition that brought him to power and presided over the launch of a new political party that eliminated the biggest threat to his dominance.

It appeared to be a masterstroke except that the TPLF was not going to fade away quietly. In a country that is as ethnically divided as it is distrusting of the other, the TPLF became an active volcano that could erupt without warning. And it did – after nearly two tenuous years of reported covert attacks, Abiy’s government delivered what became the death knell. In any ordinary nation, there would be some merit to the announced postponement of national elections in the midst of a global pandemic that had infected millions, but Ethiopia is no ordinary nation. This is a country that turns off the internet at will, kills journalists who are considered dissenters, and maintains one of the most sophisticated spy networks of any nation on earth. In Ethiopia, trust is premium. Therefore, there was no basis for the TPLF or any other group to assume that the postponement of elections was anything other than a ploy by Abiy Ahmed to illegitimately extend his government’s tenure. Chaos was inevitable.

Image source: AP Photo/Saudi Press Agency

So what should a Noble Peace Prize-winning Prime Minister do to stabilize a nation on the edge of conflict? What would be expected of a leader who presided over the calming of decades-long fraught relations between his nation and its closest neighbour, Eritrea? Anything but the deployment of the military within its own borders, you would say, but Ethiopia is not that simple to understand. Having traded words heavily and each party having accused the other of illegitimate actions bordering on treason, a Nobel Peace Prize was not going to be the answer. Uncommon leadership would be, yet it was not forthcoming.

Could Abiy have done more to prevent conflict? Could he have de-escalated tensions arising from the north with a recourse to dialogue over the blasts of rockets? Could he have governed in a more inclusive manner, so as to minimize the potential for a political eruption? As difficult as it might seem, the answer has to be yes. In politics, there must be no impossible situations for which the only recourse is conflict. That is the eternal burden of political leadership – setting aside all counter-arguments to pursue peace at all cost. But if Abiy would have followed this path, he would have found no role model in Nigeria’s Muhammadu Buhari.

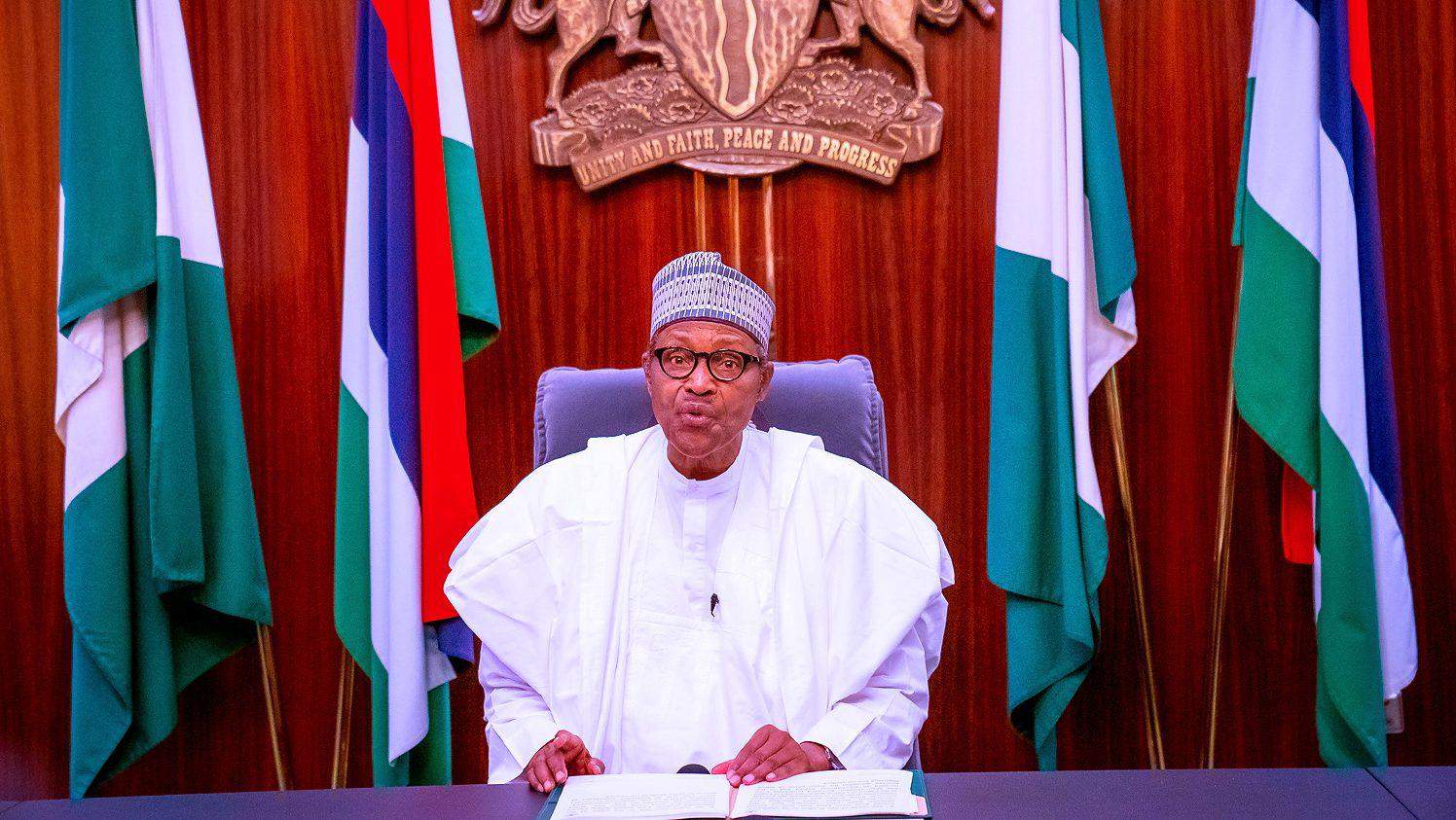

The events leading up to the latest #EndSARS protests in Nigeria did not receive the widest attention, but they have gnawed for decades. Police brutality seems to be par for the course in most countries, but it takes a different dimension in Nigeria – an under-trained, under-resourced and under-motivated public security outfit collides with a disgruntled youthful generation determined to forge economic independence on its own terms in an underperforming economy caught in a global pandemic. Nigerians have never trusted the Police Force and decades of blind eyes turned by public leaders to the plight of the Police have done nothing to help. Policemen are left to fend for themselves from the proceeds of their daily street harassment campaigns, and that’s just how it goes. Equip a special tactical unit with the mandate to stop and search supposed criminals and you ignite a ticking bomb. The Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) had been an uncontainable menace for years, and their excesses only got worse by the day.

Allegations of harassment, extortion, rape and indiscriminate murder trailed its officers nationwide, so what should have been the response of the Buhari-led government in the wake of yet another round of protests by frustrated citizens? Empathy, you would say. There was the semblance of it for a minute when the disbandment of SARS was announced, but as in Ethiopia, trust in politicians comes at a premium in Nigeria. The longer the protests went on, the shorter the fuse burned in the corridors of power. In the blink of an eye, a curfew was announced, the military was deployed, innocent protesters were killed and the lies kicked in. The twists and turns in the public statements issued by the government of Lagos state, the leaders of the army and the incompetent federal ministers who addressed the media would confuse Sherlock Holmes, but the focus here is on President Buhari.

Image Source: Nigerian Presidency via Reuters

Could he have done more to calm tensions with protesting youth before the crisis escalated? Could he have vehemently addressed the excesses of police officers and committed to speedy reforms in a manner that demonstrated genuine empathy for citizens? Could he have spoken as the father of a nation when he belatedly took to television to commiserate primarily with the few police officers who had lost their lives? By demonstrating disdain for his people and launching a vendetta against the brave souls who dared to expose his administration’s failings to the world (including CNN), he appears to be following in the footsteps of a man who has ruled his own nation since just after Buhari’s military regime came to an end three and half decades ago. One could say that Major General Muhammadu Buhari who orchestrated the military coup that brought him to power in 1983 was an inspiration for Yoweri Museveni who did the same in Uganda in 1986, and now the favour has been returned.

Uganda under Museveni has descended dramatically from a seeming economic miracle to a place of terror for dissenters. Much has been documented about Museveni’s tactics of stifling free press, quashing opposition political movements and repeated constitutional amendments to guarantee his never-ending hold on power. After signing the 2017 Constitutional Amendment Bill that removed the age limit on eligibility for contesting the presidency, he effectively guaranteed that he could rule the country for the rest of his life. One of the people determined to forestall that possibility is popular musician turned parliamentarian, Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu (known as Bobi Wine). Having suffered numerous arrests, physical torture and endless harassment by state security forces, Bobi Wine’s campaign for the presidency in 2021 has energized his base, sometimes beyond the boundaries of logic.

When Bobi Wine’s motorcade rolled into the streets of Luuka in eastern Uganda on Wednesday 19th November, it was decidedly igniting a violation of the government-imposed cap of 200 people at political rallies. With hundreds flocking after his vehicles while he raised a fist through the roof of his car, he appeared indomitable. That was until security forces swooped in and arrested him for the second time this month. The ensuing violence across the country has left more than 37 dead and several injured. It was only the latest turn in a political battle for the survival of democracy in Uganda.

Image source: STRINGER/AFP via Getty Images

However, while aggrieved citizens have argued that the cap on public gatherings is an attempt to stifle political opposition (and it may well be so), there is no justification for Bobi Wine’s refusal to encourage social distancing at his rallies. When people have been aggrieved for generations, it is understandable that defying public directives could be seen as an act of political liberation in itself, but the standards are higher for a person who aspires to the highest office. If Bobi Wine would one day lead Ugandans, he may well start shedding the toga of “ghetto president”, and demonstrate respect for public health guidelines. The stakes are higher now.

Africa’s leadership deficit has been the bane of our democratic progress to date, and it threatens to retain a stranglehold on our future. If Buhari and Museveni are guaranteed to not rule forever, could we look to Abiy Ahmed and Bobi Wine for better leadership? Could we expect that a new class of politicians would emerge who demonstrate not just competency in governance, but respect for human rights, care for the lowest class of citizens and decency in public dealings? Will there be a time when leaders do not indiscriminately mobilize the military against citizen uprisings as we have seen in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Uganda this month? Will there ever be an African leader who is skilled at de-escalating conflict? Will that day ever come?

Recent Comments