Should We Congratulate Mr. Kagame?

The dust has now settled on the thousand hills of Rwanda, and the next seven (or seventeen?) years have been decided: Paul Kagame remains president. That was never really in doubt, anyway. He had declared at a political rally on July 14th that the elections were a forgone conclusion, and he was absolutely correct. There was no opposition, or rather, there were no grounds for an opposition to thrive. Since the famed referendum in 2015 through which 98% of voters reduced the length of presidential terms from seven to five years, granting only an extension for a certain Paul Kagame for a possible third term and two further five-year terms if it pleased him, it was clear (in case there had been any doubt), that the names Kagame and Rwanda would be sung in unison for at least another generation.

No African leader polarizes opinion quite like Paul Kagame: he is fiercely loved and deeply suspected at the same time. He is the sterling image of a new breed of dynamic inspiring leadership, yet cast in the same mould of ‘authoritarian’ god-like rulership with which nearly every African is very familiar. He speaks and sounds like the future, yet he acts just like the past and the present. Over the past two decades, he had been celebrated endlessly by western media who marvelled at how one man almost singlehandedly could transform a war-ravaged country into an oasis of peace and prosperity, but the exact same journalists are now sounding the alarms about his tactics. All of a sudden, the messiah is the villain. So, should we congratulate Mr. Kagame on his victory, or should we be genuinely worried about its implications?

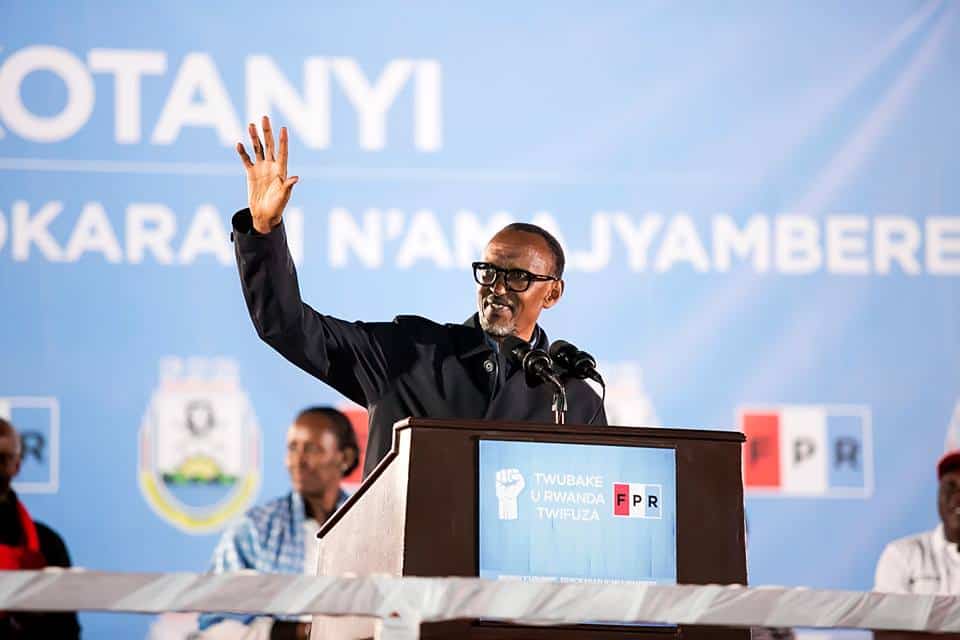

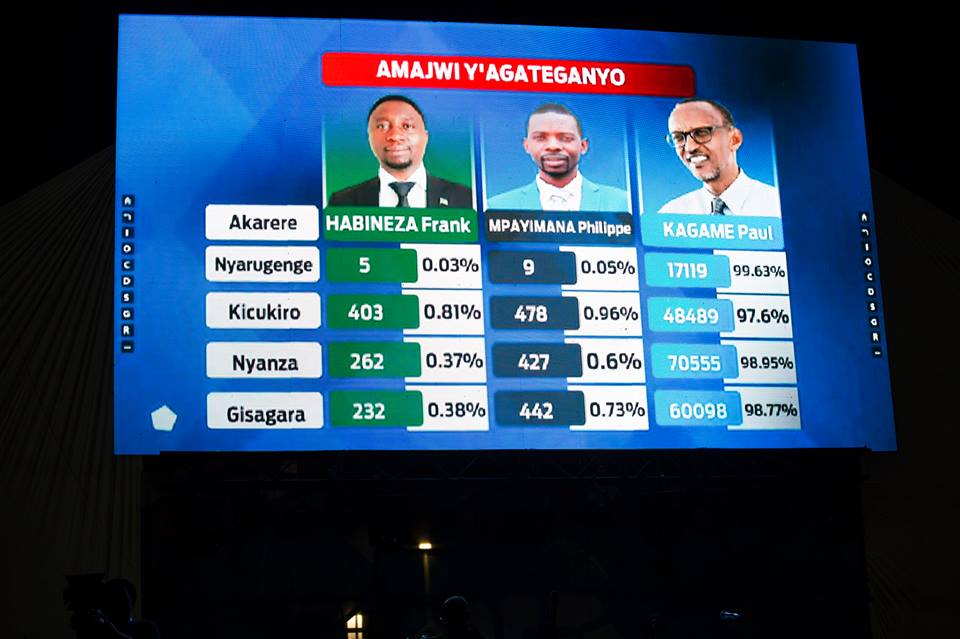

Anyone who doubts that Mr. Kagame is genuinely loved in Rwanda is probably deluded; there is no question that he has earned his status in the country. While a 99% electoral victory is extremely far-fetched in any other country of the world, not so in Rwanda. There could be no substantial allegations of electoral fraud or voter intimidation at the polls; the country literally bows at the feet of a really gaunt figure who governs nearly every aspect of political, social and economic life. While his closest challenger, Frank Habineza managed to attract up to 500 people to his last campaign rally, Kagame’s was bursting at the seams with more than 200,000. He had been accused of suppressing the opposition by arresting challengers, harassing and imprisoning anyone who spoke out publicly against him, stifling the media, and employing just about every tactic in the book to ensure that the errant weeds of political opposition were dealt with before they got a chance to sprout.

But perhaps this is all unfair criticism of a man whose only interest can be said to be the longterm sustainability of peace and prosperity in his country. Many have argued that the clamour for more democratic freedoms in Rwanda is premature, considering the fragile nature of the country’s history. Many have gone as far as to challenge the very premise of democracy in a system that seems to be working just fine; “if the people love Kagame and he is working tirelessly to uplift the country economically, then why change that”? Others have criticized western governments for employing highhanded tactics to attempt to further influence domestic affairs in Africa, citing the examples of Libya and similar countries that have struggled to find stability after western intervention. Perhaps Kagame is just what Rwanda needs, and perhaps Africa as a whole. Maybe other governments should be learning from him.

The fears expressed by African citizens are well-founded, however; no one who has ruled beyond their first and second terms in any African country has retained popularity. In essence, it is downhill from here, if history is a reliable guide. Will Kagame be any different? Will he eventually release his stranglehold on the country after he has driven Rwanda to a hilltop of economic prosperity? Will Rwandan citizens retain their love for him over time? Will he manage to build institutions with established processes that serve the many, rather than the few? Will he dispel the cloud of oppression that seems to envelope the entire country? Will the sudden disappearances of political opponents cease? Will there be a free press at some point?

Maybe democracy indeed is overrated. Maybe it doesn’t matter what foreigners think, as long as Rwandan citizens appear to be happy. Maybe it doesn’t matter if nine of 11 political parties endorsed Paul Kagame and refused to put forward candidates in the last elections. Maybe it is okay for Kagame to rule straight on until he turns 76 in 2034. Maybe it will be in the best interest of Rwanda to not upset the apple cart. And maybe the psychological impact of bowing to an emperor-figure is exactly what about 12 million Rwandan citizens need for the foreseeable future. Maybe the country would have eventually found its own rhythm by 2034, and if not, they could always amend the constitution again and permit him a few more years. Maybe we should congratulate Mr. Kagame, or maybe we should be really concerned about what we have never imagined.

One thing is for sure, we have seen this before: in the north, east, west and southern regions of the continent, beloved leaders have transformed into draconian rulers over time, but no one has done it with a subtle smile, a firm voice and a powerful social media engine. But maybe Mr. Kagame is different. Time will tell, but can we really afford that gamble yet again?

Faith Abiodun is Executive Director of Future Africa

Recent Comments