by Faith Abiodun | Dec 9, 2017 | OPINION, SPOTLIGHT

In recent weeks, Libya has been the focus of attention within the global community for the recent exposure of the mass slave trade of predominantly black African men. News outlets and social media have revealed how these men were being sold for roughly $400 and various pictures have depicted the extent of their maltreatment. All this comes after a CNN investigative journalist team released footage of material from this past month, which then sparked all the attention and consequently the Libyan government’s denunciation of the slave trade.

Source: CNN

For many people across the world, this may have come as a shock because it was not at the forefront of the societies affected, yet it does not mean the communities did not know. As unacceptable as it is, slavery is not new to the region around and by extension the African continent. What is new is the revelation of the extreme human rights abuse. By this, I mean the practice of enslaving Africans is a system that exists that several communities know of, yet the experiences are never exposed at this level. As the Director of the organisation Ivorians Living Abroad, Issiaka Konate, and former slave Diaby Baba said, “The recent discovery by CNN is in fact an open secret that people have known about”; an open secret that has led to an organisation such as Ivorians Living Abroad stating that they found 595 Ivorians within the Libyan slave network.

This slave trade in Libya can be seen as example of how societies ignore the need to address negative qualities, perhaps under the assumption that ‘out of sight is out of mind’, which then equates to out of existence. Instead the atrocity underscores the importance of addressing such situations and circumstances, particularly within the various societies across the continent.

Source: CNN

It is critical not to discredit the importance of drawing the global community’s attention to the slave trade. In fact, the detailed display of this mass ‘underground’ network has raised awareness. As with all issues, awareness is a crucial first step to opening a doorway to many possibilities in regards to actions and resolutions. Now that this has been achieved, creating discussion platforms may be beneficial. These platforms need to engage the tensions that have been present even prior to this news. The tension of how nations north of the Sahara, such as Libya. interact and perceive themselves in relation to nations south of the Sahara, such as Côte d’Ivoire and vice versa. When it comes to economic relations between States, it is visible that there is an existing relationship. An example is the involvement of Moroccan corporations supporting Ivorians in developing their infrastructure.

In understanding how the relationship between such countries is complicated, especially once hierarchies are also included, we allow for these discussions to be as cognizant as possible in approaching how to attain reconciliation and a Pan African approach. Discussion, as valuable as that is, does not constitute a conclusion to such a matter. This issue by default of being on the African continent and involving African countries, is therefore an African issue. As a result there should be an expectation for strong African contribution towards action in resolving and reconciling the slave trade. By this I mean, the responsibility should not only lie with the International Organisation for Migration (OIM) along with other international bodies. Arguably organisations such as Ivorians Living Abroad have stepped up to be a part of this work. As States, Libya has denounced the actions that have occurred through the slave trade and Rwanda is exemplar in providing itself as a possible refuge to 30,000 migrants who suffered in the slave conditions.

There are also other agents taking action which have not been recognised, yet there are many more who have the possibility to also contribute even in the minutest of forms. As individuals and particularly for those who have a form of investment on the continent, it may be our responsibility to ask the questions that hold organisations, societies, governments and leaders accountable. Therefore, it cannot be said that as an individual there is no role in assuring the resolution of this issue or the next. Because this slave trade is just another example on the list of issues that have been allowed to grow to an incomprehensible capacity because it was not addressed. Out of sight, out of mind, out of existence is not a working solution and it would be rare that ever will be.

Arnold Sanginga is Director of Programs at Future Africa.

by Faith Abiodun | Oct 27, 2017 | OPINION

As the drumbeats leading up to Nigeria’s next presidential election grow louder, I have been in reflection about the role that people like me play in shaping the destiny of a nation. In under two years, Nigeria will have a new (or the same) president, and citizens would likely have resorted to the regular routine of complaints following dashed hopes yet again. It has become our national ritual since 1999 to drum up huge expectations in the run-up to our pilgrimage to the polls, and then complain bitterly almost immediately afterwards. We are not alone in this process, but Nigerians have a habit of believing our problems are the worst.

Participants at the Future Africa 30-Under-30 Forum in Accra, Ghana

I have had the good fortune of traveling to countries in the north, east, west and southern regions of the continent and I have found the political cultures to be eerily similar everywhere. Our political affairs are highly sensationalized, sparsely intelligent, and mostly pedestrian. The absence of political ideology or much of a national development roadmap precludes the evolution of a truly dynamic political party culture. What results is opposition on the pure basis of opposition and quest for power rather than presenting a counter approach to economic growth and social development. In Nigeria, this is best illustrated by the criss-crossing of candidates between the All Progressives Congress (APC) and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), both of whom parade about the same candidates as we have seen for the last 18 years.

But they are not the problem, neither are the very poor and uneducated electorate who will vote en masse and with enthusiasm once they have received their bags of rice, gallons of oil and campaign t-shirts. I have thought long and hard about the few times when I have cast votes in state and national polls and wondered how enthusiastic I was, and the answers don’t leave me with joy. I have not been excited about Nigerian political candidates for a long time; too few who are close to the centre of political attention speak with purpose or present feasible ideas, and the very few who sound intelligible hardly stand a realistic chance. Being caught in this straight, and in spite of the best efforts of the energetic group of young Nigerians who have championed a political awakening in some of the country’s youth, I have done what most people around me do – complain bitterly about the paucity of credible candidates, strip down the threadbare policy proposals which make it to the newspapers, and decide to probably vote anyway because half loaf is better than none.

Participants at the Future Africa 30-Under-30 Forum in Accra, Ghana

Educated, empowered citizens like me who have the luxury of choosing our level of political involvement are the albatross of our continent. Many choose to abstain altogether from the electoral process because “politics is dirty”, “politicians are all greedy and corrupt”, and because we can afford to educate ourselves abroad, take vacations once a year and drive good enough cars. Because we consider ourselves to have one or two options, we choose to not be as invested as is necessary in the daily political lives of our nations; we leave that to the touts, grassroots politicians, and greedy nincompoops who have dominated our political reality for too long. So, next time you are moved to complain about the political stagnation around this continent, remember that no single individual will change the fortunes of a country; it takes the power of a collective to destroy or build a nation. For better or for worse, our fortunes are tied together.

Faith Abiodun is Executive Director of Future Africa

by Faith Abiodun | Aug 24, 2017 | OPINION

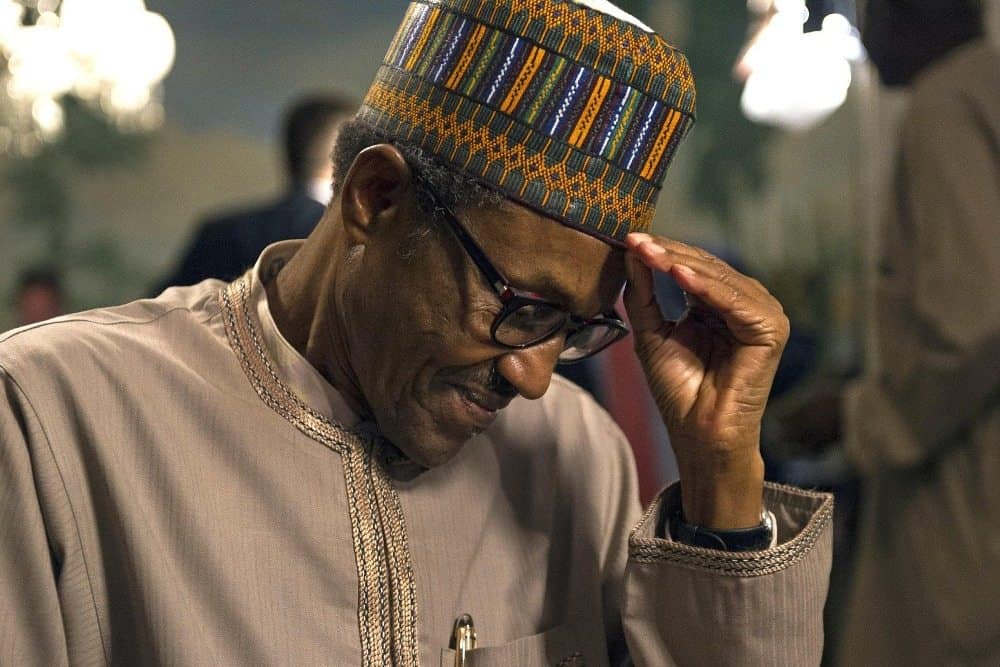

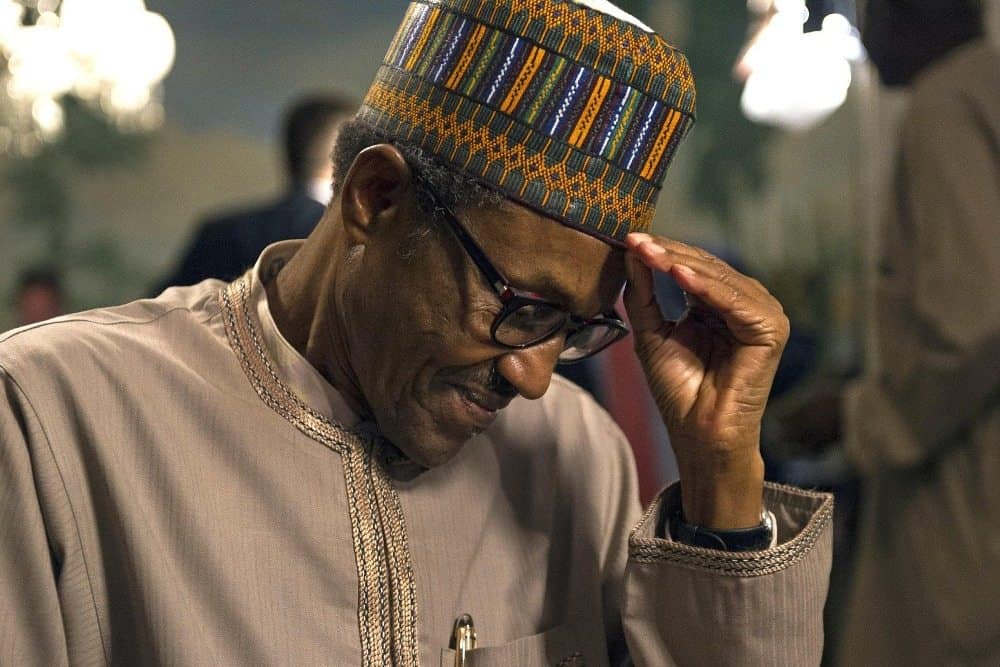

When Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari announced through his spokesman in June 2016 that he would be undertaking a 10-day trip to the United Kingdom (UK) to treat an ear infection, the uproar was unbelievable. He was widely derided by many who accused him of perpetuating the same medical tourism which he had campaigned against. A former president of the Nigerian Medical Association, Dr. Osahon Enabulele claimed that Buhari’s action undermined the local health system in the country and contributes to capital flight which was in excess of $1bn. People questioned how grievous the ear infection could be that no Nigerian doctor was found worthy to examine. Ignoring the uproar, Buhari left for the UK.

When his spokesman, Femi Adesina, wrote on January 19th, 2017 that President Buhari would head to the UK once again as part of his annual vacation, with a tacit line that the President will undergo “routine medical check-ups”, the public discomfort was unquestionable. It was becoming evident that the suspicions about the President’s fragile state of health were more than rumours; reports of prostate cancer were not too far from the media, and prominent voices called for the President to speak the truth about his condition, but they went unheeded. What was publicly presented as a three-week vacation quickly turned into a seven-week period of discomfort and hushed tones. Rather than question the prolonged absence of their President, Nigerians were admonished to pray for his quick recovery. When he eventually returned to Nigeria, Buhari failed to answer questions about his health or to resume work in his office, he only mentioned that he had “never felt so sick since he was a young man”, but claimed to have recovered.

Source: Buzznigeria.com

It was therefore no surprise, but nonetheless utterly frustrating when it was announced less than two months after that he was returning to the UK for further treatments. Once again, Nigerians were told to ask no questions about his exact condition, but to continue to pray for his quick recovery. In a country which houses more religious centres than institutions of learning, and one which favours prayer above reasonable action, patience was fast running out. Questions were asked about who was funding the President’s treatment, but the questioners were roundly lectured in respect for elders by the unpopular Minister of Information, Lai Mohammed whose common retort was that there was no cause for alarm and that the President would return home when his doctors released him. His Personal Assistant on Social Media, Lauretta Onochie, then went on national TV to scold Nigerians for being disrespectful in asking persistent questions about the President’s health. For three months, the charade over the President’s health was played out on the pages of newspapers, on national TV and on social media sites before photos suddenly began to emerge from Abuja House in London. First it was the Vice President who visited for his photo-opp, then some state governors, then party chieftains, then the President’s social media team, then the Senate President and the House Speaker, and then Pastor E.A. Adeboye. It seemed as though the queues from Lagos/Abuja to London couldn’t get any longer. In all these photos, Buhari appeared to be healthy and smiling, while his grovelling subjects almost couldn’t believe their good fortune to be in his presence.

After so much uproar, street protests, vandalism of property, and endless social media memes, President Buhari is now back in Nigeria; and he has made one unconvincing TV appearance to show that he is alive, but the drama was not over. Apparently someone in Aso Rock had released a stream of undetected rats into his office during the past three months such that the furniture in the President’s office had been eaten up, warranting the President to work from home indefinitely. Who really comes up with these cock-and-bull stories? There are many more creative ways to express the President’s preference for working from home while he continues his recovery, but … rats?

Perhaps the most upsetting component of this charade around the President’s health is the gross disrespect to citizens who are funding the President’s care. To think and say that Nigerians do not have a right to know the health status of the person whom they elected to lead them is absolute foolishness. To cover that up by saying that the presence of an acting president suffices is further foolishness. Yes, no one can predict the nature of illnesses and no one is eternally protected from them, but it is wrong to assume that citizens do not have the right to information about what ails their leader. It has already been mooted that the President might return to the UK again for further treatment, and that will not be a surprise when it happens. He is an old man. What will be most disappointing is if his media team continues to spew out such disrespectful statements to the citizens whose taxes are responsible for his aircraft maintenance, aviation fuel, hospital bills, and the numerous other costs of bed rest.

May wisdom prevail.

Faith Abiodun is the Executive Director of Future Africa

by Faith Abiodun | Aug 10, 2017 | OPINION

The dust has now settled on the thousand hills of Rwanda, and the next seven (or seventeen?) years have been decided: Paul Kagame remains president. That was never really in doubt, anyway. He had declared at a political rally on July 14th that the elections were a forgone conclusion, and he was absolutely correct. There was no opposition, or rather, there were no grounds for an opposition to thrive. Since the famed referendum in 2015 through which 98% of voters reduced the length of presidential terms from seven to five years, granting only an extension for a certain Paul Kagame for a possible third term and two further five-year terms if it pleased him, it was clear (in case there had been any doubt), that the names Kagame and Rwanda would be sung in unison for at least another generation.

No African leader polarizes opinion quite like Paul Kagame: he is fiercely loved and deeply suspected at the same time. He is the sterling image of a new breed of dynamic inspiring leadership, yet cast in the same mould of ‘authoritarian’ god-like rulership with which nearly every African is very familiar. He speaks and sounds like the future, yet he acts just like the past and the present. Over the past two decades, he had been celebrated endlessly by western media who marvelled at how one man almost singlehandedly could transform a war-ravaged country into an oasis of peace and prosperity, but the exact same journalists are now sounding the alarms about his tactics. All of a sudden, the messiah is the villain. So, should we congratulate Mr. Kagame on his victory, or should we be genuinely worried about its implications?

Anyone who doubts that Mr. Kagame is genuinely loved in Rwanda is probably deluded; there is no question that he has earned his status in the country. While a 99% electoral victory is extremely far-fetched in any other country of the world, not so in Rwanda. There could be no substantial allegations of electoral fraud or voter intimidation at the polls; the country literally bows at the feet of a really gaunt figure who governs nearly every aspect of political, social and economic life. While his closest challenger, Frank Habineza managed to attract up to 500 people to his last campaign rally, Kagame’s was bursting at the seams with more than 200,000. He had been accused of suppressing the opposition by arresting challengers, harassing and imprisoning anyone who spoke out publicly against him, stifling the media, and employing just about every tactic in the book to ensure that the errant weeds of political opposition were dealt with before they got a chance to sprout.

But perhaps this is all unfair criticism of a man whose only interest can be said to be the longterm sustainability of peace and prosperity in his country. Many have argued that the clamour for more democratic freedoms in Rwanda is premature, considering the fragile nature of the country’s history. Many have gone as far as to challenge the very premise of democracy in a system that seems to be working just fine; “if the people love Kagame and he is working tirelessly to uplift the country economically, then why change that”? Others have criticized western governments for employing highhanded tactics to attempt to further influence domestic affairs in Africa, citing the examples of Libya and similar countries that have struggled to find stability after western intervention. Perhaps Kagame is just what Rwanda needs, and perhaps Africa as a whole. Maybe other governments should be learning from him.

The fears expressed by African citizens are well-founded, however; no one who has ruled beyond their first and second terms in any African country has retained popularity. In essence, it is downhill from here, if history is a reliable guide. Will Kagame be any different? Will he eventually release his stranglehold on the country after he has driven Rwanda to a hilltop of economic prosperity? Will Rwandan citizens retain their love for him over time? Will he manage to build institutions with established processes that serve the many, rather than the few? Will he dispel the cloud of oppression that seems to envelope the entire country? Will the sudden disappearances of political opponents cease? Will there be a free press at some point?

Maybe democracy indeed is overrated. Maybe it doesn’t matter what foreigners think, as long as Rwandan citizens appear to be happy. Maybe it doesn’t matter if nine of 11 political parties endorsed Paul Kagame and refused to put forward candidates in the last elections. Maybe it is okay for Kagame to rule straight on until he turns 76 in 2034. Maybe it will be in the best interest of Rwanda to not upset the apple cart. And maybe the psychological impact of bowing to an emperor-figure is exactly what about 12 million Rwandan citizens need for the foreseeable future. Maybe the country would have eventually found its own rhythm by 2034, and if not, they could always amend the constitution again and permit him a few more years. Maybe we should congratulate Mr. Kagame, or maybe we should be really concerned about what we have never imagined.

One thing is for sure, we have seen this before: in the north, east, west and southern regions of the continent, beloved leaders have transformed into draconian rulers over time, but no one has done it with a subtle smile, a firm voice and a powerful social media engine. But maybe Mr. Kagame is different. Time will tell, but can we really afford that gamble yet again?

Faith Abiodun is Executive Director of Future Africa

Recent Comments