by Faith Abiodun | Jan 30, 2018 | OPINION

By Faith Abiodun

Just as the 30th African Union (AU) Summit was wrapping up in Addis-Ababa, Ethiopia last week, news broke via some thorough investigative work by Le Monde, that China’s gift to the AU six years ago was serving more purposes than initially assumed. China, the darling of the continent, has tremendously grown in influence across Africa over the past two decades, and there is no bigger symbol of that than the sprawling complex which houses the pinnacle of the continent’s aspirations – the AU’s headquarters.

African Union headquarters, courtesy of China Source: http://www.zambianobserver.com

It has been alleged that in gifting the AU headquarters to Africa in 2012, China had cleverly left a “backdoor” into the computer network in the building, allowing it to access the AU’s data at will. This had been undetected since 2012, until it was discovered recently that there seemed to be a peak in data usage between midnight and 2am when no one was in the office, but daylight had broken in Shanghai. Of course, China denies that it had anything to do with this strange discovery, but the AU has moved quickly to install its own servers and carry out a clean sweep of its headquarters with technical expertise from Algeria.

Firstly, there should be no surprise here, though we are justified to be alarmed. He who pays the piper dictates the tune. The mere existence of the AU headquarters – the continent’s unifying symbol – as a “gift” from China has always been a puzzle; what was in it for China? The building is still maintained by Chinese workers to this day, and even its elevator symbols are written in Chinese. This is bothersome. The overt Chinese presence on the continent in construction and business has been attributed to the availability of generous loans with affordable interest rates, as well as willing partnership for development. After all, a bird in hand is worth 10 in the bush, since the West had started to play hard ball with African leaders. But to have an entire spy operation underway from within the AU’s internet infrastructure is another level of audacity.

Heads of State and Government at the 30th AU Summit. Source: UNECA

So, where do we go from here? I believe that this is time to re-assess Africa’s relationship with China, and capitalize on this breach of trust to re-write the modus operandi. China must be made to come clean with its intentions, and not explain this away with a slap on the wrist. This is major espionage! When the US government was caught red-handed spying on Germany and Brazil, a full apology was demanded; the US government (grudgingly by Donald Trump) has equally employed a special counsel to investigate alleged Russian interference in its last elections; Africa (an entire continent) cannot be seen to be dealing with this quietly. But do we really have the gut to call China out on its game? The same country that effortlessly exports ivory out of the continent in spite of numerous anti-poaching campaigns globally will likely get away easily with this major security breach. This is the biggest shame of all.

Until the day comes when we are truly independent of foreign interests, it appears that we will remain nothing more than a pawn in this global game of chess. We need to look inwards and think deeply.

PS: Who else found it curious that this investigative work was carried out by Le Monde (a French publication) and not an African media agency? Sigh!

Faith Abiodun is Executive Director of Future Africa

by Faith Abiodun | Jan 11, 2018 | OPINION

On December 28th, 2017, Equatorial Guinea confirmed that it had foiled a coup allegedly involving mercenaries from Sudan, Chad, Central African Republic and Cameroon. In this intervention, one mercenary was killed and the others are yet to be captured. Since the mercenaries were found entering the country from the border with Cameroon, officials from Equatorial Guinea have accused Cameroon of supporting the coup, thus increasing tension between the two countries. These accusation are not unfounded as they stand on the basis that Cameroon had supported another failed coup in 2004. As a response to this, Equatorial Guinea blocked its border with Cameroon, which has left many people stranded for the past two weeks.

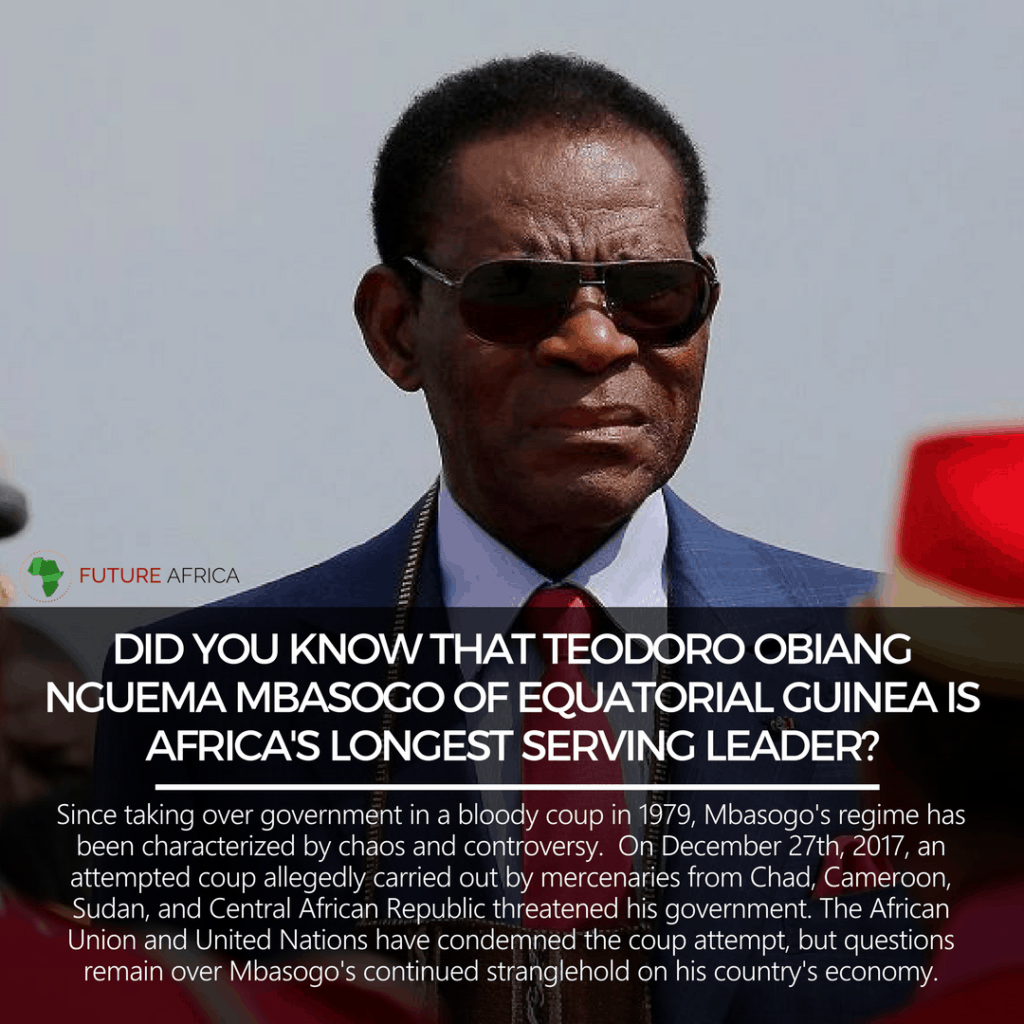

President Teodoro Mbasogo. Source: www.voanews.com

If Cameroon had any responsibility in orchestrating such a coup, then it could be perceived that Cameroon is intentionally undermining the sovereignty of another nation. By Cameroon meddling in the affairs of Equatorial Guinea, it conveys a message to citizens that the government is incapable of carrying out its duties. At the same time, it inhibits the government from having the opportunity of performing their responsibility in maintaining the functionality of an independent nation. The outcome of the coup has strained the relationship between the two countries, causing distrust and discord in their engagement. As a government, one of the primary responsibilities is to ensure the nation’s security and stability internally and across its borders. Therefore, Equatorial Guinea deciding to block the border shared with Cameroon, is the government ensuring the security of the nation from a neighbouring country it does trust during this period of time.

On the other hand, Cameroon’s actions should also be applauded. Even though the coup did fail, it did return the attention to the duration of time that Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo has been President of Equatorial Guinea. President Mbasogo assumed the presidential seat in 1979 and is now one year shy of four decades as President, which makes him the longest serving President on the African continent. President Mbasogo is not the only African leader that represents a practice of ‘President for Life’, as Uganda recently repealed the age limit enabling President Yoweri Museveni to seek another term. Ironically, other leaders that have retained power for decades are Idriss Deby (Chad), Omar al-Bashir (Sudan) and even Paul Biya (Cameroon). This may show that these countries were not in fact interested in providing democracy an opportunity to prosper. However, 2017 was a year that saw two long-time leaders lose their position of power. In Angola, former President Jose Eduardo dos Santos vacated his seat after 38 years. Then in Zimbabwe, a coup forced former President Robert Gabriel Mugabe to resign after 37 years. This may have been part of the inspiration for the coup. Regardless, of their own personal interests, Central African Republic, Chad, Sudan and Cameroon’s involvement in the coup has challenged a leadership that has undermined democratic practices and upheld the rhetoric of Presidents for life.

Ultimately, this coup presents concerns on how do other nations intervene and hold other countries accountable, without infringing on the targeted country’s sovereignty and imposing their own interests. It is disappointing that leaders across the African continent continue to follow in these democratic malpractices, with leaders such as Joseph Kabila (Democratic Republic of Congo) and several others joining this list as preventers of leadership transitions. However, the hope is that this failed coup in Equatorial Guinea exerts pressure on President Mbasogo, and by extension other leaders fitting the same criteria. Regardless of the outcome, it is without a doubt that the actions of every party involved will affect the citizens the most. Already, migrants, particularly merchants have voiced the damage the blockade of the border has done for their business and livelihoods. Eventually, the government will revert back to normal practices but the questions are burning: How long does President Mbasogo have left? Could 2018 be the fall of his regime? And which leader would be next?

Ultimately, this coup presents concerns on how do other nations intervene and hold other countries accountable, without infringing on the targeted country’s sovereignty and imposing their own interests. It is disappointing that leaders across the African continent continue to follow in these democratic malpractices, with leaders such as Joseph Kabila (Democratic Republic of Congo) and several others joining this list as preventers of leadership transitions. However, the hope is that this failed coup in Equatorial Guinea exerts pressure on President Mbasogo, and by extension other leaders fitting the same criteria. Regardless of the outcome, it is without a doubt that the actions of every party involved will affect the citizens the most. Already, migrants, particularly merchants have voiced the damage the blockade of the border has done for their business and livelihoods. Eventually, the government will revert back to normal practices but the questions are burning: How long does President Mbasogo have left? Could 2018 be the fall of his regime? And which leader would be next?

Nteranya Arnold Sanginga is Director of Programs at Future Africa

by Faith Abiodun | Jan 3, 2018 | EDITORIAL

When the news broke in September 2017 that the Ugandan Parliament was considering a bill to eliminate age limits for presidential aspirants, it sounded incredulous. After all, it was only a year before then that the sitting president, Yoweri Museveni, had won an unprecedented fifth term in office, having controversially scrapped the limit to presidential terms in 2005 to permit an elongation of his stay in power. Since taking control of Uganda in 1986, 73-year old Museveni has demonstrated time and again that he has no intentions of relinquishing his stranglehold on the country’s future, and he does so with the enthusiastic support of his cronies in parliament.

Ugandan legislators brawl in parliament during debate on the bill. Source: James Akena/Reuters

Enacted in 1995, the Ugandan constitution had stipulated that anyone younger than 35 or older than 75 will be ineligible to serve as President. That was purportedly to prevent political neophytes or aged and jaded parasites from ruling the country, but Museveni seems intent on negating all of that. Despite the protests of activists and the gallant efforts of opposition politicians, 317 legislators voted in favour of the controversial bill on December 20th, 2017, against the wishes of the 97 opposing legislators and the majority of citizens and religious leaders who made their voices heard. In his year-end address, Museveni said “Parliament enabled us to avoid the more complicated paths that would have been required. We cannot under-cook the destiny of Africa”. He eventually signed the bill into law on December 27th, 2017.

While it cannot be argued that Museveni is justified as a citizen in wanting to retain his presidency, and that there is some logic in the statement credited to MP Moses Balyeku that “age should not be a factor that hinders the rights and freedom of any Ugandan to vie for the post of a President”, it belies common sense that such narrow-minded constitutional amendments are being driven against the demographic realities on the continent. By the time the next elections are due in 2021, Museveni will be 77 years old. In a country where the median age of citizens is 15.8 years, Museveni is clearly swimming against the tide of nature. Shamefully, he is being paddled along by politicians who are more interested in their own personal aggrandisement than they are in the future of the country. Like Paul Kagame in Rwanda, Museveni has taken the irresponsible path and further dimmed the hope for responsible leadership in Africa.

Conclusively, it disgusts the senses to realize that the elongation of Museveni’s political ambition seems to be his preoccupying thought less than two years into his current term, when there is so much work to be done to lift Uganda from being one of the poorest countries in the world. If five terms of Museveni’s leadership has brought Ugandans no closer to economic freedom, what hope is there that a sixth term will make a difference? It might have been hoped that the “Mugabe treatment” will prove instructive for other geriatric African rulers, but perhaps it will take the “Mugabe outcome” for the message to sink in.

We still have a lot of work to do.

Recent Comments